Preventive Hormonal Health

![shutterstock_1957857619 HORMONES[1004].jpg](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/de014f_ad67dac86581473c9515b3b156ebea9b~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_343,h_229,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/de014f_ad67dac86581473c9515b3b156ebea9b~mv2.jpg)

The healthyher.life team supports a holistic approach to managing women’s hormonal healthcare. Our goal is to help our members be well-informed about their hormonal health, by providing them with evidence-based integrated health information that includes the current standard of medical care advised by qualified physicians, clinical insights from licensed allied health professionals (naturopathic doctors, nurse-practitioners, nutritionists, psychotherapists) and new health innovations that will be soon coming to market. Always consult with your doctor regarding your medical condition, diagnosis, treatment, or to seek personalized medical advice.

Hirsutism: Understanding Excessive Hair Growth In Women

By Susan Johnson

Reviewed by: Rina Carlini, PhD

January 7, 2025

Why do some women experience excessive hair growth on areas of their face and body where it's not usual for most women?

This could be due to hirsutism, a medical condition that causes excess hair growth, affecting approximately 5–10% of women worldwide. While it doesn’t severely affect physical health, excessive hair in unwanted areas can lead to significant social discomfort, psychological stress, and feelings of embarrassment for women, especially in social settings and the workplace, where it can affect their confidence and impact career growth opportunities. [1]

While hirsutism is often dismissed as a minor cosmetic issue, it can be a sign of abnormal androgen activity in the body, stemming from underlying endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or, in rare cases, more serious medical conditions. Beyond the physical symptoms, the emotional toll it can have on a person can be profound—impacting a woman's self-esteem, relationships, and mental health.

Hirsutism Is More Than Just Abundant Hair Growth

Hirsutism is characterized by excessive hair growth on certain parts of the body, especially in areas where men typically grow hair, such as the chin, upper lip, chest, back, and abdomen. This hair is usually coarse, curly, and pigmented (terminal hair) rather than the fine, soft, and lightly pigmented hair (peach fuzz) commonly present on a woman’s body.

While the primary symptom of hirsutism is the excessive growth of dark hair, women with more body hair than what’s considered normal shouldn’t assume they have the condition. A physician or healthcare professional will be able to provide an accurate diagnosis after assessing the symptoms and extent of hair growth.

What Causes Hirsutism In Women?

Hirsutism is often a symptom of other conditions and typically results from hormonal imbalances or disorders that increase the level of androgens in the body. [2]

Androgens are a group of hormones that are present in all people. However, men and people assigned male at birth naturally produce more of these androgen hormones than do females. When an adult woman has high androgen levels, it triggers a pattern of physical and sexual development that’s typical of males, including overstimulation of hair follicles, leading to excessive hair growth. This process is called virilization. [3]

Apart from hirsutism, other signs of virilization include:

-

Acne

-

Oily skin

-

A deep or masculine voice

-

Balding (temporal hair recession)

-

Increased musculature

-

Decreased breast size

-

Irregular menstruation

-

Enlarged clitoris

Other conditions that can cause hirsutism include:

-

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) – The leading cause of hirsutism, where nearly 70-80% of all people diagnosed with PCOS develop hirsutism. Those with PCOS have an imbalance of sex hormones. Over time, it leads to excess hair growth, abnormal menstruation, weight gain, and challenges with fertility. [4]

-

Cushing’s Syndrome – Cortisol is a hormone that can affect various organs controlling the integumentary system–hair, skin, nails, glands, and nerves. In people with Cushing's syndrome, there is a high level of cortisol. Prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels can disrupt androgen production. [5]

-

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH) – A genetic condition where the adrenal glands produce abnormal amounts of steroid hormones, including androgens and cortisol. [6]

-

Androgen-Secreting Tumors – Rare ovarian or adrenal tumors can lead to high levels of male hormones, leading to rapid-onset hirsutism. [7]

-

Medications – Some drugs, like anabolic steroids, testosterone, minoxidil, cyclosporine, danazol, and phenytoin, can cause hirsutism. [8]

Sometimes, hirsutism can be familial, meaning it is inherited and isn’t associated with any underlying medical condition. You might be more susceptible to developing hirsutism if you have a family history of conditions that cause it. In addition, the chances of developing hirsutism increases with age, especially after menopause, due to hormonal imbalances. [1]

Lastly, genetics significantly influences hair color, thickness, and density or distribution of hair follicles. For instance, women from regions like the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and the Indian subcontinent often naturally have darker and thicker body or facial hair. So, in these populations, more hair on the face and body is typically considered normal and may not be a sign of hirsutism.

Diagnosing Hirsutism

A physician would initially conduct a physical examination to determine the extent of uncommon hair growth, which is assessed using the Ferriman-Gallwey scale. [9]

The Ferriman-Gallwey scale examines nine areas of your body where male-pattern hair is likely to develop due to high androgen influence–the upper lip, chin, chest, upper abdomen, lower abdomen, upper arms, thighs, upper back, and lower back/buttocks. Each area is scored on a scale from 0-4 based on the density and thickness of terminal hair. Low numbers indicate mild hirsutism and higher numbers indicate severe male-pattern hair growth.

The scores from all nine areas are added to determine a total score between 0 and 36. Typically, the scores are interpreted as follows:

-

≤8: Normal (no significant hirsutism)

-

8-15: Mild hirsutism

-

>15: Moderate to severe hirsutism

While the Ferriman-Gallwey score is a helpful diagnostic tool, it has some limitations. For instance, due to how genetics influence hair growth patterns, the threshold for what constitutes "normal" may vary slightly depending on factors like ethnicity. Here are the scores that are considered normal based on ethnicity.

-

Black or white (Caucasian) people – 8

-

Mediterranean, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern people – 9 or 10

-

Asians – less than 2

So, in clinical practice, this scoring system is often combined with blood tests (which help measure androgen levels) and diagnostic imaging tests (CT, ultrasound, and X-ray) if an underlying cause is suspected.

Managing Hirsutism: Treatment Options

Managing hirsutism typically involves addressing its underlying cause. Generally, weight loss is the first step in treatment. According to studies, obesity can increase androgen production, worsening hirsutism. [10] [11] Hence, losing even 5% of the body weight can lower androgen levels and prevent excessive hair growth. [12]

In some cases, especially if the patient has mild hirsutism that is spontaneous or that happens without a known cause, cosmetic measures may be sufficient to manage it, such as shaving, bleaching, waxing, or plucking. Hair removal options like electrolysis (to destroy hair roots one by one) and laser (to destroy hair cells with a lot of pigment) can also be administered.

In other cases, a topical or systemic therapy might be necessary to treat hirsutism. [13] These options may include:

-

Birth control pills / oral contraceptives – The first-line treatment for hirsutism, they lower androgen levels by suppressing ovarian activity.

-

Androgen-suppressing medications – Medications like spironolactone, finasteride, and flutamide block androgens from binding to hair follicles, reducing hair thickness and growth rate.

-

Low-dose steroid medications – Used if overactive adrenal glands are causing hirsutism. Adrenal glands produce sex hormones, including cortisol.

-

Insulin-lowering medications – High insulin levels trigger ovaries to produce androgens. Metformin and pioglitazone improve insulin sensitivity, thereby indirectly lowering androgen production. However, they aren’t used as a first-line treatment due to their significant side effects.

-

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists – Rarely used, they suppress ovarian androgen production. Since they require injections, they can be expensive.

-

Eflornithine skin cream – A topical product that slows down hair growth. It takes 6 to 8 weeks to see noticeable results.

The proper treatment option for hirsutism will depend on its severity. Medications for treating hirsutism often take weeks or months to show any noticeable results; lifestyle modifications through weight management are also beneficial and can give more impactful results that endure over your life.

Always consult with your family physician or nurse practitioners for any serious and persistent concerns about your medical condition, diagnosis, and treatment, or to seek personalized medical care. Join the Healthyher.Life as a community member and connect with others in our Community Forum who have had similar experiences with managing hirsutism.

References:

[1] Sachdeva S. Hirsutism: evaluation and treatment. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55(1):3-7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.60342. PMID: 20418968; PMCID: PMC2856356. [PubMed]

[2] Rosenfield, R. L. (2005). Hirsutism. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(24), 2578-2588. [The New England Journal of Medicine]

[3] Spritzer PM, Marchesan LB, Santos BR, Fighera TM. Hirsutism, Normal Androgens and Diagnosis of PCOS. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Aug 9;12(8):1922. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12081922. PMID: 36010272; PMCID: PMC9406611. [PubMed]

[4] Spritzer PM, Barone CR, Oliveira FB. Hirsutism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Management. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(36):5603-5613. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160720151243. PMID: 27510481. [ResearchGate]

[5] Haouat, E., Ben, S. L., Kamoun, I., Zrig, N., Turki, Z., & Ben, S. C. (2012, May 1). Androgens profile in Cushing. https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0029/ea0029p953 [Endocrine Abstracts]

[6] Baskin HJ. Screening for Late-Onset Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia in Hirsutism or Amenorrhea. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(5):847–848. doi:10.1001/archinte.1987.00370050043007 [JAMA Network]

[7] Varma T, Panchani R, Goyal A, Maskey R. A case of androgen-secreting adrenal carcinoma with non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013 Oct;17(Suppl 1):S243-5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.119585. PMID: 24251173; PMCID: PMC3830319. [PubMed]

[8] Patel A, Malek N, Haq F, Turnbow L, Raza S. Hirsutism in a female adolescent induced by long-acting injectable risperidone: a case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(3):PCC.12l01454. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12l01454. PMID: 24171143; PMCID: PMC3795580. [PubMed]

[9] Bhns. (n.d.-a). https://bhns.org.uk/ccs_files/web_data/Resources/Diseases%20(severity%20scoring)/Hirsuitism.pdf [British Hair and Nail Society]

[10] Mazza, E., Troiano, E., Ferro, Y., Lisso, F., Tosi, M., Turco, E., Pujia, R., & Montalcini, T. (2024). Obesity, Dietary Patterns, and Hormonal Balance Modulation: Gender-Specific Impacts. Nutrients, 16(11), 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111629 [MDPI]

[11] Pasquali R. Obesity and androgens: facts and perspectives. Fertil Steril. 2006 May;85(5):1319-40. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.054. PMID: 16647374.[PubMed]

[12] Zapała B, Marszalec P, Piwowar M, Chmura O, Milewicz T. Reduction in the Free Androgen Index in Overweight Women After Sixty Days of a Low Glycemic Diet. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2024 Jan;132(1):6-14. doi: 10.1055/a-2201-8618. Epub 2024 Jan 18. PMID: 38237611; PMCID: PMC10796197. [PubMed]

[13] Hunter MH, Carek PJ. Evaluation and treatment of women with hirsutism. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jun 15;67(12):2565-72. PMID: 12825846. [PubMed]

Testosterone as a Supplemental Form of Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT): The Facts You Should Know

By Susan Johnson

Reviewed by Rina Carlini, PhD

October 16, 2024

Menopause is a natural phase in a woman’s life that comes with a host of uncomfortable symptoms, which can be classified broadly into four main categories: 1) Genitourinary Syndrome (GSM), 2) Vasomotor symptoms and related heart health issues, 3) musculoskeletal issues, and 4) Cognitive issues. Of these, GSM typically presents itself with low libido, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), vaginal atrophy, frequent urination and sometimes incontinence. This can lead to poor quality of life and social stress for your relationships.

There has been much discourse about testosterone being a worthwhile supplement for managing GSM (the genitourinary symptoms of menopause), and there’s a growing number of women who are demanding it from their OB/GYN physicians as a part of their Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT). However, testosterone supplementation isn’t a solution that’s safe or suitable for all women.

Testosterone And Menopause

Testosterone is commonly believed to be a male hormone. However, women also make this hormone, but in lower amounts than men.

The ovaries and the adrenal glands (located on top of the kidneys) produce testosterone, which plays a vital role in libido, bone strength, sexual response, cognitive performance, energy levels, and more.

Though women produce three to four times as much testosterone as estrogen before menopause [1], their testosterone levels gradually decrease as they age. During menopause, the testosterone levels in most women fall to about one-quarter of what they were at their peak during their 20s. [2] A sudden decrease in testosterone levels also happens when both the ovaries are removed. [3]

When the hormone levels fall, women start experiencing depression, lower energy, and lower sex drive (libido).

How Does Testosterone Help Treat The GSM Symptoms?

Testosterone is best known for improving libido. However, testosterone receptors are present all over the body, so its effects are far-reaching.

The hormone plays a vital role in strengthening nerves and arteries in the brain, thereby contributing to mental sharpness and clarity and protecting against memory loss. It also stimulates the release of serotonin and dopamine, improving overall mood and feelings of pleasure. It further boosts overall energy levels by improving muscle mass and bone strength. [4]

Perhaps this is why a lot of women take testosterone as part of their hormone replacement therapy (HRT), reporting: [5]

-

Increased libido

-

Improved energy

-

Enhanced muscle strength

-

Improved focus and mental clarity

-

Improved sleep

Who Should Use Testosterone, And Who Shouldn’t?

Due to the lack of long-term safety data for cardiovascular and breast outcomes, testosterone isn’t licensed for use in women, except in Australia, where Androfeme (1% of testosterone cream) is approved. [6]

However, specialist doctors do prescribe testosterone supplementations to women whose sex drive doesn’t improve with MHT. This is because the NICE Menopause Guideline (NG23) [7] and the British Menopause Society (BMS) [8] state that a trial of HRT should be given to women before considering testosterone supplementation.

Testosterone can be taken as a tablet/capsule. However, it isn’t recommended due to its negative impact on blood cholesterol levels. Transdermal delivery, such as gel, cream, patches, or implants, is generally considered the safest in doses that reflect young women’s testosterone levels.

Side Effects

Adverse effects of testosterone in women are uncommon, given the supplementations are provided within the physiological range. The most common side effects include:

-

Hair growth

-

Acne

-

Weight gain

These effects are reversible and can be addressed either by discontinuing the use of testosterone or by lowering its dosage. More severe but rare side effects include:

-

Alopecia

-

Deepening of voice

-

Clitoral enlargement

Typically, testosterone has to be prescribed for 3-6 months before its efficacy can be thoroughly evaluated. [9] Furthermore, an annual re-evaluation of ongoing usage is performed just like with the standard HRT to weigh the pros and cons of long-term usage.

Women with an active liver or cardiovascular disease or with a history of hormone-sensitive breast or endometrial cancer should avoid testosterone usage. [10]

References:

[1] Scott A, Newson L. Should we be prescribing testosterone to perimenopausal and menopausal women? A guide to prescribing testosterone for women in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2020 Mar 26;70(693):203-204. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X709265. PMID: 32217602; PMCID: PMC7098532.

[2] Skiba MA, Bell RJ, Islam RM, Handelsman DJ, Desai R, Davis SR. Androgens During the Reproductive Years: What Is Normal for Women? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Nov 1;104(11):5382-5392. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01357. PMID: 31390028.

[3] Rocca WA, Shuster LT, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, Gostout BS, Geda YE, Melton LJ 3rd. Long-term effects of bilateral oophorectomy on brain aging: unanswered questions from the Mayo Clinic Cohort Study of Oophorectomy and Aging. Womens Health (Lond). 2009 Jan;5(1):39-48. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.1.39. PMID: 19102639; PMCID: PMC2716666.

[4] Bassil N, Alkaade S, Morley JE. The benefits and risks of testosterone replacement therapy: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009 Jun;5(3):427-48. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3025. Epub 2009 Jun 22. PMID: 19707253; PMCID: PMC2701485.

[5] Glynne S, Kamal A, Kamel AM, Reisel D, Newson L. Effect of transdermal testosterone therapy on mood and cognitive symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2024 Sep 16. doi: 10.1007/s00737-024-01513-6. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39283522.

[6] https://www.nps.org.au/assets/medicines/47d5a936-d106-46a4-9278-a53300ff76e5-reduced.pdf

[7] https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng23

[10] Davis SR. Cardiovascular and cancer safety of testosterone in women. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011 Jun;18(3):198-203. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328344f449. PMID: 21415740.

Sleep and Hormones

By Henry Xu, PhD. and Joanne Tejeda, PhD.

July 19, 2024

Reproductive hormones play a crucial role in regulating various physiological processes in women, including sleep. The interplay between estrogen and progesterone significantly influences sleep patterns and quality, with noticeable variations across different phases of the menstrual cycle, during pregnancy, and throughout menopause. These hormonal fluctuations can lead to sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, fragmented sleep, and changes in sleep patterns.

Women have a more than 40% higher risk of sleep disorders compared to men. Over 50% of menopausal women globally suffer from sleep disorders, and up to 65% of young adult women experience poor sleep quality due to factors such as irregular sleep schedules, high rates of anxiety and depression, and excessive screen time [1-3].

Keep reading to discover how reproductive hormones affect sleep patterns and uncover essential strategies to combat sleep-related issues that many women face throughout their reproductive lives.

How is Sleep affected at each stage of your menstrual cycle?

During the follicular phase, the first half of the menstrual cycle, rising estrogen levels can promote better sleep by increasing rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and enhancing overall sleep quality [4].

During the luteal phase, the second half of the menstrual cycle, estrogen levels fluctuate and drop just before menstruation, contributing to sleep disturbances. Progesterone levels increase and have a sedative effect, initially promoting sleepiness. However, as progesterone levels drop just before menstruation, women may experience premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms, including insomnia, disrupted sleep, night sweats [4].

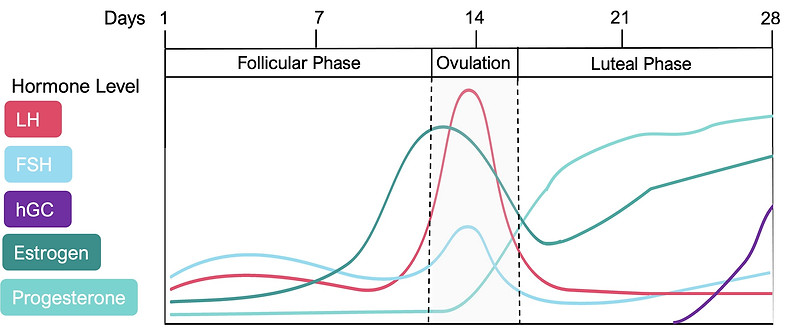

Figure 1. Hormone changes during the average 28-day menstrual cycle without a fertilization event. FSH is Follicle Stimulating Hormone and LH is Luteinizing Hormone. Shaded gray area is the Ovulation phase, which represents when you are most fertile.

Menstruation

During menstruation, women often experience specific changes in their sleep patterns due to a combination of physical discomfort and hormonal shifts. Common issues include increased sleep disturbances, such as frequent awakenings and difficulty falling asleep, primarily caused by menstrual pain, cramps, bloating, headaches and fatigue. Additionally, hormonal fluctuations during this phase can lead to mood changes, such as irritability and anxiety, which further contribute to sleep disruptions. Some women also report experiencing more vivid dreams and nightmares during menstruation. Understanding these patterns can aid in developing better sleep management strategies during this time [5].

How is sleep affected during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, sleep patterns shift significantly across each trimester [6, 7]:

-

First Trimester: increased levels of progesterone can cause excessive daytime sleepiness and frequent awakenings at night due to nausea and increased urination.

-

Second Trimester: sleep generally improves as hormone levels stabilize, although some women may still experience disruptions.

-

Third Trimester: sleep disturbances often increase again due to physical discomfort, frequent urination, and hormonal changes.

Sleep Changes During Menopause

Sleep changes during the menopause transition (e.g., perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause) are significant due to hormonal fluctuations. During perimenopause, declining estrogen and progesterone levels can cause hot flashes, night sweats, and mood swings, leading to insomnia and fragmented sleep. Menopause intensifies these symptoms, further disrupting sleep and increasing the risk of sleep disorders such as sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome.

In menopausal women, Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) can help alleviate sleep disturbances by stabilizing hormone levels. However, HRT is not suitable for everyone and should be considered carefully with medical guidance.

In post-menopause, while some symptoms may stabilize, many women continue to experience sleep disturbances due to persistent hot flashes, increased anxiety, and other health changes [6, 7].

How Women’s Sleep and Hormones Impact Memory

Sleep plays a crucial role in cognitive functions, including memory consolidation, which is the process of transforming short-term memories into long-term ones. For women, hormonal changes throughout their reproductive lives can significantly impact sleep quality and, consequently, memory [6].

Estrogen

Estrogen has been shown to have neuroprotective effects, which can enhance cognitive functions, including memory. It promotes the growth and survival of neurons, enhances synaptic plasticity, and increases neurotransmitter levels.

As estrogen levels decline during menopause, many women report difficulties with memory and other cognitive functions. HRT has been found to mitigate some of these cognitive declines, although its use must be carefully considered due to other health risks.

Progesterone

Progesterone's impact on memory is more complex and can vary. Some studies suggest it may impair certain types of memory, particularly verbal and spatial memory, while others indicate it might support memory consolidation during sleep. High levels of progesterone during the luteal phase can sometimes lead to difficulties in memory and concentration, often referred to as "brain fog."

Research Insights on Estrogen and Progesterone Effects on Memory

Recent research highlights that estradiol (a form of estrogen) strengthens brain cell mechanisms crucial for memory formation and retrieval. Estradiol can induce rapid changes in brain cells within minutes to hours, essential for enhancing memory consolidation. This demonstrates estradiol's powerful and swift impact on the brain. Estrogen's memory-enhancing ability suggests potential for treating cognitive decline associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases [8]. In addition, new findings reveal progesterone's rapid inhibitory role on memory during navigational tasks [9].

Strategies for Improving the Sleep Quality

Improving sleep quality is important for overall health and well-being. Here are some practices that women can adopt to get better sleep [6, 7]:

-

Establish a consistent sleep schedule – going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, even on weekends, helps regulate your body’s internal clock.

-

Create a relaxing bedtime routine by engaging in calming activities like reading. Avoid screens (phones, tablets, computers, TV) at least an hour before bedtime as the blue light can interfere with melatonin production.

-

Avoid heavy meals before bed as they a can cause discomfort and interfere with sleep

.

-

Limit caffeine and alcohol intake.

-

Manage your stress by practicing relaxation techniques such as medication, breathing exercises to help calm the mind.

-

Regular physical activity can promote better sleep. Aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise most days of the week but avoid vigorous exercise close to bedtime.

For women suffering from chronic insomnia, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) may be beneficial. CBT-I includes components such as sleep hygiene education, stimulus control, sleep restriction, and cognitive restructuring. Unlike sleeping pills, CBT-I has long-lasting effects without the risk of side effects. If medication is necessary, options like benzodiazepines and melatonin receptor agonists are available but should be used short-term to avoid potential dependency [10]. In addition, medications such as dopamine agonists and anti-seizure drugs can be used to treat specific disorders like Restless Legs Syndrome.

If sleep problems persist, it may be helpful to consult a healthcare provider or a sleep specialist to rule out sleep disorders and to find the best treatment solution for you.

References

[1] Salari, Nader et al. “Global prevalence of sleep disorders during menopause: a meta-analysis.” Sleep & breathing = Schlaf & Atmung vol. 27,5 (2023): 1883-1897. doi:10.1007/s11325-023-02793-5

[2] Fatima, Yaqoot et al. “Exploring Gender Difference in Sleep Quality of Young Adults: Findings from a Large Population Study.” Clinical medicine & research vol. 14,3-4 (2016): 138-144. doi:10.3121/cmr.2016.1338

[3] Phillips, Barbara A et al. “Sleep disorders and medical conditions in women. Proceedings of the Women & Sleep Workshop, National Sleep Foundation, Washington, DC, March 5-6, 2007.” Journal of women's health (2002) vol. 17,7 (2008): 1191-9. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0561

[4] Alana M C Brown, Nicole J Gervais, “Role of Ovarian Hormones in the Modulation of Sleep in Females Across the Adult Lifespan”, Endocrinology, Volume 161, Issue 9, September 2020, doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa128

[5] Baker, Fiona C, and Kathryn Aldrich Lee. “Menstrual Cycle Effects on Sleep.” Sleep medicine clinics vol. 13,3 (2018): 283-294. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2018.04.002

[6] Nicole J. Gervais, Jessica A. Mong, Agnès Lacreuse, “Ovarian hormones, sleep and cognition across the adult female lifespan: An integrated perspective”,Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, Volume 47, 2017, Pages 134-153, doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2017.08.002

[7] Harrington YA, Parisi JM, Duan D, Rojo-Wissar DM, Holingue C, Spira AP. “Sex Hormones, Sleep, and Memory: Interrelationships Across the Adult Female Lifespan”, Frontier in Aging Neuroscience, 2022 Jul 14, Volume 14 - 2022, doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.800278

[8] Luine, Victoria N., and Maya Frankfurt, “Estrogenic Regulation of Recognition Memory and Spinogenesis.” Karyn M. Frick (ed.), Estrogens and Memory: Basic Research and Clinical Implications (2020): 159–169. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190645908.003.0011

[9] Lacasse, Jesse M et al. “Progesterone rapidly alters the use of place and response memory during spatial navigation in female rats.” Hormones and behavior vol. 140 (2022): 105137. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2022.105137

[10] Abad, Vivien C, and Christian Guilleminault. “Diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders: a brief review for clinicians.” Dialogues in clinical neuroscience vol. 5,4 (2003): 371-88. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2003.5.4/vabad

What are Uterine Fibroids?

By Henry Xu PhD., Joanne Tejeda, PhD.

July 12, 2024

Uterine fibroids, also known as leiomyomas or myomas, are non-cancerous growths in the uterus composed of muscle and fibrous tissue. They can range in size from a pea to as large as a melon.

Globally, there are 226 million cases of uterine fibroids, with the highest prevalence among women aged 40-50. About 80% of women will develop uterine fibroids in their lifetime.

In the United States, about 26 million women aged 15 to 50 that are diagnosed with fibroids [1]. By age 50, nearly 80% of Black women and 70% of white women will develop fibroids. While experiences vary, about 25% of women with fibroids suffer from severe symptoms requiring treatment [2].

What Causes Uterine Fibroids?

The exact cause of uterine fibroids is not fully understood, but several factors are believed to contribute to their development, these include [3]:

1. Hormones that regulate the menstrual cycle, estrogen and progesterone, promote the growth of fibroids. When hormone levels drop after menopause, fibroid growth tends to decrease [4].

2. Evidence suggests that family genetics is a contributing factor as uterine fibroids tend to occur within the family [5].

3. Race is a key factor for uterine fibroids, as African-American women are 3-times more likely to develop fibroids and at a younger age compared to women of other racial groups [6].

4. Obesity has been linked to an increase in the risk of fibroids [7].

5. Vitamin D deficiency is also associated with increased risk of uterine fibroids [8].

6. Women with high blood pressure typically have a significantly higher risk of developing uterine fibroids [5].

Symptoms of Uterine Fibroids [2]:

-

Heavy menstrual bleeding

-

Prolonged periods (lasting more than a week)

-

Iron Deficiency Anemia

-

Pelvic pain or pressure

-

Frequent urination

-

Difficulty emptying the bladder

-

Constipation

-

Backache

-

Leg pains

-

Reproductive issues, such as infertility or pregnancy complications

Diagnosis of Uterine Fibroids:

Diagnosis typically begins with taking the patient’s history and identifying symptoms related to uterine fibroids. A pelvic exam is then conducted to check for irregularities in the shape and size of the uterus. In certain cases, blood tests may be conducted to rule out other causes of symptoms, like anemia from heavy bleeding.

Imaging tests are crucial for an accurate diagnosis. Ultrasound is the primary imaging technique used due to its ability to visualize fibroids and assess their size, number, and location. Saline infusion, involving the injection of a salt solution into the uterus, is often used to create clearer ultrasound images [9].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is another valuable tool, especially for detailed mapping of fibroids, which is essential for treatment planning. MRI also helps distinguish fibroids from other pelvic conditions. Other traditional imaging techniques include hysteroscopy, which allows direct visualization of the uterine cavity using a thin, lighted scope, aiding in the identification of fibroids. [10].

Treatments of Uterine Fibroids:

Medications

For mild symptoms, over-the-counter pain relief can be used. Hormonal treatments, such as oral contraceptives or special injections that lower hormone levels, can also help shrink fibroids [4].

Non-Invasive Procedures

Radiofrequency ablation is a procedure that uses radio energy and heat to remove uterine fibroids. It is performed with a small, energized probe that is passed through the vagina and cervix into the uterus, guided by ultrasound throughout the procedure [11].

Minimally Invasive Procedures

Uterine artery embolization (UAE) is a treatment in which surgeons inject small particles into the arteries surrounding the fibroid to cut off its blood flow, causing it to shrink [12].

Radiofrequency ablation can also be used in minimally invasive procedures, where laparoscopic scopes are inserted into small incisions to guide the procedure [13].

Traditional Surgical Procedures

An abdominal myomectomy involves making an incision in the abdominal wall to access the uterus and surgically remove fibroids from its surface.

For women with severe symptoms who do not plan on having more children in the future, hysterectomy is used as a last resort [14].

Treatment of uterine fibroids can be time-consuming. Many women often go through multiple doctor visits before being diagnosed, and up to 32% of diagnosed women wait more than 5 years before seeking treatment [2]. Improved access to educational resources is needed to help guide women in their journey when seeking treatment for uterine fibroids.

New Medical Innovations

Medical device innovators are constantly developing new treatment tools for the non-invasive removal of uterine fibroids. Radiologist Dr. Elizabeth David at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto is working on shrinking fibroids using high-intensity focused ultrasound guided by MRI. She recently completed a clinical trial in which 90% of patients reported being symptom-free after the procedure. [15].

Helpful Resources:

Living with fibroids can be challenging, with women reporting an average loss of 5.1 work hours per week due to the condition [1].

The Uterine Fibroids Toolkit: A Patient Empowerment Guide by the Society for Women's Health Research is a fantastic resource, offering information to help you understand your condition and make informed decisions.

Join the Healthyher.Life community to connect with others who have had similar experiences with fibroids.

References:

[1] Lou, Zheng et al. “Global, regional, and national time trends in incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability for uterine fibroids, 1990-2019: an age-period-cohort analysis for the global burden of disease 2019 study.” BMC public health vol. 23,1 916. 19 May. 2023, doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15765-x

[2] Society for Women's Health Research. *Uterine Fibroids Toolkit: A Patient Empowerment Guide*. Society for Women's Health Research, 2023.

[3] Stewart, E A. “Uterine fibroids.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 357,9252 (2001): 293-8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03622-9

[4] Bulun, Serdar E. “Uterine fibroids.” The New England journal of medicine vol. 369,14 (2013): 1344-55. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1209993

[4] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “Management of Symptomatic Uterine Leiomyomas.” ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 228, July 2021.

[5] Stewart, E A et al. “Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review.” BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology vol. 124,10 (2017): 1501-1512. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14640

[6] Eltoukhi, Heba M et al. “The health disparities of uterine fibroid tumors for African American women: a public health issue.” American journal of obstetrics and gynecology vol. 210,3 (2014): 194-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.008

[7] Pavone, Dora et al. “Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Uterine Fibroids.” Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology vol. 46 (2018): 3-11. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.09.004

[8] Baird, Donna Day et al. “Vitamin d and the risk of uterine fibroids.” Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) vol. 24,3 (2013): 447-53. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828acca0

[9] Palheta, Michel Santos et al. “Reporting of uterine fibroids on ultrasound examinations: an illustrated report template focused on surgical planning.” Radiologia brasileira vol. 56,2 (2023): 86-94. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2022.0048

[10] De La Cruz, Maria Syl D, and Edward M Buchanan. “Uterine Fibroids: Diagnosis and Treatment.” American family physician vol. 95,2 (2017): 100-107.

[11] Christoffel, Ladina et al. “Transcervical Radiofrequency Ablation of Uterine Fibroids Global Registry (SAGE): Study Protocol and Preliminary Results.” Medical devices (Auckland, N.Z.) vol. 14 77-84. 3 Mar. 2021, doi:10.2147/MDER.S301166

[12] Gupta, Janesh K et al. “Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids.” The Cochrane database of systematic reviews ,5 CD005073. 16 May. 2012, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005073.pub3

[13] Milic, Andrea et al. “Laparoscopic ultrasound-guided radiofrequency ablation of uterine fibroids.” Cardiovascular and interventional radiology vol. 29,4 (2006): 694-8. doi:10.1007/s00270-005-0045-9

[14] Guarnaccia, M M, and M S Rein. “Traditional surgical approaches to uterine fibroids: abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy.” Clinical obstetrics and gynecology vol. 44,2 (2001): 385-400. doi:10.1097/00003081-200106000-00024

[15] Single Arm Study Using the Symphony -- MRI Guided Focused Ultrasound System for the Treatment of Leiomyomas (HIFUSB). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03323905. Updated July 9, 2024. Accessed July11, 2024 https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03323905

The Silent Burden: Iron Deficiency and Anemia in Women

By Henry Xu, Ph.D, Joanne Tejeda, Ph.D

original post: July 2, 2024 | updated: Sept 16, 2024

Iron is an essential mineral for your body, playing crucial roles in your immune and cardiovascular systems. It is mainly used to produce a protein called hemoglobin, which carries oxygen in red blood cells. When your body lacks sufficient iron, it can result in iron deficiency anemia, a common health issue affecting many women worldwide. Globally, more than 33% of women aged 15-49 suffer from anemia, with over 800 million cases due to iron deficiency – twice as many compared to men [1]. In Canada, an estimated 29% of women aged 19-50 experience iron deficiency anemia. [2]. These conditions can lead to various health complications, impacting overall quality of life and productivity.

In this article, we explore how to identify iron deficiency anemia and manage iron levels. Catching symptoms of anemia early and taking steps to maintain healthy iron levels are crucial for women's health.

What Causes Iron Deficiency Anemia in Women?

Iron deficiency is a condition where the body does not have enough iron to produce hemoglobin. When this condition worsens and there isn’t enough oxygen in red blood cells, it can result in iron deficiency anemia, potentially leading to tissue and organ damage. [3]. Several factors contribute to the increased prevalence of iron deficiency in women. Women of reproductive age are particularly susceptible to iron deficiency due to blood loss during menstruation [4].

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) – where bleeding from the uterus is abnormal – affects up to 25% of women of reproductive age. The most common subtype of AUB is heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia), which significantly increases iron loss [5]. An ongoing comprehensive review by Dr. Michelle Zeller from McMaster University is examining the effectiveness of iron treatments for AUB [6]. This research aims to improve our understanding of how iron treatments can enhance health outcomes for women with iron deficiency due to AUB.

Iron deficiency is also a common issue for expecting and postpartum mothers. The increased iron demands during pregnancy and lactation can lead to the rapid depletion of iron stores in the mother’s body, especially if the pregnancy is not supported with additional iron through nutrients or supplements.

An unbalanced diet with limited consumption of iron-rich foods, such as red meat, poultry, and fish, is another common factor leading to iron deficiency. Vegetarian and vegan diets may also pose a risk if not carefully managed to include alternative iron sources. In addition, several gastrointestinal conditions, such as celiac disease, Crohn's disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBS), and those who have undergone gastric bypass surgery, can decrease iron absorption, leading to iron deficiency.

Common Symptoms of Iron Deficiency Anemia

The symptoms of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia can vary in severity and may include [4, 7]:

%20(1).png)

The Impact of Iron Deficiency Anemia on Women’s Health

Adolescent Women

During these developmental years, bodies are rapidly changing and growing, making iron even more important. Without enough iron, adolescents can feel tired, weak, and have trouble concentrating, impacting their performance and daily activities. Additionally, as girls begin menstruating, they lose iron each month, increasing their risk of deficiency. Ensuring sufficient iron is essential for maintaining their energy levels, supporting growth, and promoting overall well-being [8].

Adult Women

Iron is equally important for adult women. Without healthy levels of iron, they might feel tired, weak, or even dizzy, greatly impacting their work and social life. Women periodically lose iron during menstruation, making it even harder to meet the body’s iron needs. Heavy and prolonged athletic activities also increase iron loss through sweating [4].

Pregnant Women

Iron needs increase significantly to support fetal development and increased blood volume. Pregnant women are often advised to take prenatal vitamins that include iron to prevent deficiency. Monitoring iron levels throughout pregnancy is essential to ensure both maternal and fetal health. Iron-deficient mothers can encounter complications during pregnancy, including preterm delivery and low birth weight [4].

Perimenopausal Women

During perimenopause, women may experience irregular or increased menstrual volume. These changes can contribute to increased iron loss and result in iron deficiency anemia. Some symptoms of perimenopause, such as fatigue and headaches, might overlap with iron deficiency symptoms, making it important for perimenopausal women to regularly check their blood iron levels to avoid developing anemia [4].

Postmenopausal Women

Postmenopausal women generally have a lower risk of iron deficiency due to the cessation of menstrual blood loss. However, they can still be affected by insufficient dietary iron or gastrointestinal issues. Regular health check-ups and maintaining a balanced diet are important for preventing iron deficiency in this age group [4].

How is Iron Deficiency Anemia Diagnosed?

Diagnosing iron deficiency anemia involves a combination of clinical evaluation and laboratory tests [3], including:

1. A Complete Blood Count (CBC), which is a comprehensive blood test used to evaluate overall health and detect a variety of disorders, including anemia, infection, and many other diseases. The CBC measures several components and features of your blood, such as Red Blood Cells (RBCs), White Blood Cells (WBC), Hemoglobin (Hgb), Hematocrit (Hct), and Platelets.

2. A Serum Ferritin Test that measures the level of ferritin in your blood. Ferritin is a protein that stores iron in your body's cells, and the amount of ferritin in your blood reflects the amount of stored iron. This test helps to evaluate your body's iron levels and diagnose conditions related to iron deficiency or excess. Low ferritin levels indicate low iron stores, which can lead to iron deficiency anemia.

Interpretation of Serum Ferritin Test Results

Table adapted from NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [9, 10]

3. A Serum Iron and Total Iron-Binding Capacity (TIBC) test that measures the amount of circulating iron and the blood’s capacity to bind iron, respectively. Low serum iron and high TIBC levels are indicative of iron deficiency.

4. The Transferrin Saturation Test used to evaluate how much iron is bound to transferrin, the protein that transports iron in the blood. Low transferrin saturation indicates insufficient iron supply.

Treatment and Prevention

The primary goals in treating iron deficiency anemia are to replenish iron stores and address any underlying causes [3,4]. Dietary changes are usually a fundamental step in treatment and prevention. Heme iron, found in animal products, is more readily absorbed by the body compared to non-heme iron in plant-based foods. Including vitamin C-rich foods in meals can enhance non-heme iron absorption.

For women with dietary restrictions or needing additional iron, ferrous sulfate and other oral supplements are commonly used to treat iron deficiency. While effective, these supplements can cause gastrointestinal side effects like constipation and nausea, which can be mitigated by taking them with meals and consuming fiber. For those who cannot tolerate oral iron or have severe deficiencies, intravenous iron infusions may be necessary, especially in cases of absorption issues. Always consult your doctor to determine which supplement option is best for you.

If you're persistently tired or noticing other symptoms, consult a healthcare professional about iron deficiency anemia. Proactive steps like eating a balanced diet and getting regular check-ups can help maintain healthy iron levels and ensure your well-being.

New Update: September 2024 Iron Deficiency Revised Guidelines for Ontario

New guidelines introduced in Ontario on September 9, 2024, have raised the thresholds for diagnosing iron deficiency, allowing for earlier detection and improved treatment. Previously, ferritin levels below 10 to 15 micrograms per litre were flagged as abnormal, but many patients with symptoms of iron deficiency went undiagnosed due to these low thresholds. The updated standards now raise the baseline to 30 micrograms per litre for adults and 20 for children, aligning with global research and evidence dating back to 1992. This change is expected to significantly improve patient care, especially for women, marginalized communities, and those at higher risk due to conditions like heavy menstrual bleeding.

Below is the updated table reflecting the new serum ferritin level thresholds:

Interpretation of Serum Ferritin Test Results ( Per New Ontario Guidelines)

These guidelines are a major step forward in addressing health equity and improving outcomes for those who have long suffered from undiagnosed iron deficiency.

Don’t Miss Out – Access the Video Recording Now!

On July 24th, 2024, Healthyher.Life had the privilege of hosting Dr. Michelle Zeller, a clinical hematologist and Associate Professor at McMaster University, for an insightful Women Talking™ Wednesday event: "Iron is Essential for Your Health and Vitality – Are You Getting Enough?"

If you’re wondering whether you have unmet iron needs or how iron plays a critical role in your health, this is your chance to get informed. Dr. Zeller’s expert insights on the importance of iron and how to ensure you’re getting enough could make a real difference in your well-being.

.png)

References:

[1] GBD 2021 Anaemia Collaborators. “Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990-2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021.” The Lancet. Haematology vol. 10,9 (2023): e713-e734. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00160-6

[2] Cooper, M., Bertinato, J., Ennis, J. K., Sadeghpour, A., Weiler, H. A., Dorais, V.. “Population Iron Status in Canada: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2012-2019.” The Journal of Nutrition, Mar 2023, Volume 153:5, pp1534-1543. doi:10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.03.012

[3] Kumar, A., Sharma, E., Marley, A., Samaan, M. A., & Brookes, M. J., “Iron deficiency anaemia: pathophysiology, assessment, practical management.” BMJ open gastroenterology, 2022, Volume 9:1:e00759, doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2021-000759

[4] Percy, L., Mansour, D., Fraser, I. “Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anaemia in women.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2017, Volume 40, pp 55-67, doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2016.09.007

[5] Whitaker, Lucy, and Hilary O D Critchley. “Abnormal uterine bleeding.” Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology vol. 34 (2016): 54-65. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.012

[6] Nazaryan, H., Watson, M., Ellingham, D., Thakar, S., Wang, A., Pai, M., Liu, Y., Rochwerg, B., Gabarin, N., Arnold, D., Sirotich, E., Zeller, M. P. “Impact of iron supplementation on patient outcomes for women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Systematic reviews, Jul 2023, Volume 12:1, pp 121, doi: 10.1186/s13643-023-02222-4

[7] “Iron-Deficiency Anemia.” Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Feb. 2022, www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/iron-deficiency-anemia.

[8] Aksu, Tekin, and Şule Ünal. “Iron Deficiency Anemia in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence.” Turkish archives of pediatrics vol. 58,4 (2023): 358-362. doi:10.5152/TurkArchPediatr.2023.23049

[9] “Iron-Deficiency Anemia.” National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 24 Mar. 2022, www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/anemia/iron-deficiency-anemia.

[10] Mei, Zuguo et al. “Physiologically based serum ferritin thresholds for iron deficiency in children and non-pregnant women: a US National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) serial cross-sectional study.” The Lancet. Haematology vol. 8,8 (2021): e572-e582. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00168-X

[11] Harrison, L. (2024, September 9). Ontario's new iron deficiency guidelines may change lives: Doctors. CBC News. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/iron-deficiency-bloodwork-testing-ontario-1.7314795

HORMONES 101

Part 1: Fundamentals About Reproductive Hormone

Reviewed by Joanne Tejeda, PhD and Rina Carlini, PhD

When it comes to managing menstrual cycles, many women, and individuals with a female reproductive anatomy try not to think about it and simply power through ‘the period’ as a regular thing… it’s predictable, it’s annoying, and we want it to end as fast as possible! More often than not, we don’t have a full understanding about how our hormones influence our menstrual cycle and how hormones can change as we age. Hormone levels in our body evolve over time, starting at puberty when our period first begins, to menopause when a full year has passed with no more menstrual periods. If it sounds like an easy ride, think again – many people have experienced a kind of ‘hormonal gymnastics’ during every decade (and sometimes every month) of their lives.

Don’t worry though because healthyher.life is here with our new info-series Hormones 101, which will help explain the fundamentals of hormone health and answer those questions you’ve always wanted to ask but were afraid to. So, whether you are experiencing problems with your menstrual flow, dealing with unbearable pelvic pain, planning to get pregnant, or wondering if you’re in perimenopause, we have it covered… keep reading below😊.

What type of reproductive hormones do I have? [1], [2]

Women and individuals with female reproductive anatomy have a set of hormones that play a crucial role in regulating menstrual cycles and the activity of the reproductive organs - these are:

-

Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) – stimulates the follicles, which are the fluid-filled sacs in the ovaries that contain egg cells (a.k.a. ovum, plural ova), to produce estrogen and get the body ready to release an egg during ovulation.

-

Luteinizing Hormone (LH) – produced by the pituitary gland in the brain, LH triggers the body to ovulate (i.e., release an egg, or ovum) during your menstrual cycle. LH also helps to create a temporary and normal cyst inside the ovary after the egg has been released, which is called the corpus luteum, and also promote the release of progesterone hormone.

-

Estrogens – includes a group of natural steroid hormones released by the ovaries to help the egg mature in the ovary prior to its release. The major sources of estrogen in the body are the ovaries and the placenta (the temporary pregnancy organ that nourishes the fetus and remove waste), while much smaller amounts are secreted by the adrenal glands, as well as the male testes.

-

Progesterone – a female steroid sex hormone that is released from the corpus luteum and helps with thickening of the uterine lining during the luteal phase of your cycle (more about this explained below). The thickened endometrium (or wall lining) prepares the uterus for implantation of a fertilized egg.

-

Testosterone – the hormone responsible for maintaining general body health and sexual desire. Most of the testosterone that is made in women and individuals with a female reproductive anatomy gets converted by the body into estrogen and helps the body release an egg during ovulation.

How are my hormones involved in the menstrual cycle? [3]

Whether you are just starting to learn about your menstrual cycle, or you’ve weathered the monthly menstrual storm for a few decades, everyone should know that the average menstrual cycle for a female lasts 28 days.

The diagram in Figure 1 illustrates a normal 28-day menstrual cycle in which the levels of reproductive hormones FSH (Follicle Stimulating Hormone), LH (Luteinizing Hormone), Estrogen and Progesterone will change during each of the 3 menstrual cycle phases:

Follicular Phase → Ovulation → Luteal Phase

Below we will explain what happens to your body during each of the three phases.

Follicular Phase - Days 1 to 13 of your cycle

Days 1-7: Menstruation

The Follicular Phase begins on Day 1 with the start of menstruation (the first day of your period) where your body is shedding the cellular lining of your uterus, which is blood. During this menstruation period that lasts an average of about 5-7 days (however it can be a longer or shorter period), you may experience symptoms such as uterine cramps, bloating of your abdomen and some weight gain, tender breasts, mood swings, and irritability. Your estrogen levels are generally low during the first 7 days of the Follicular Phase. [3, 4]

Days 8-11: Production of egg cells

Immediately following the end of menstruation, your estrogen levels will start to increase as your body prepares for ovulation (the release of ova, or egg cells). The FSH and LH hormones are also increasing during this phase to stimulate the ovaries to produce egg cells. By the end of this period, the FSH hormone level decreases slightly so that only one of the egg cells continues to grow and mature.

Days 11-15: Fertility Window

Days 11 to 15 following the start of your menstruation (which is Day 1 of your cycle) is the period leading up to ovulation, or the release of a mature egg cell (ovum) and is considered the “fertility window”. During this short period of approximately 4-5 days, females will have a higher chance of becoming pregnant than any other time during your entire menstrual cycle.

Ovulation: Day 14

Your body’s FSH and LH hormones are at peak level by Day 14, which causes the ovaries to release a mature egg. You are most fertile around Day 14, which is the Ovulation phase. The LH hormone, which triggers the body to ovulate (i.e., release the egg), also helps create a temporary and completely normal cyst of cells called the corpus luteum inside the ovary after the egg (ovum) has been released. [3, 4]

Luteal phase: Day 15 to 28

Days 15-24

Following ovulation and the release of an ovum, your body’s FSH and LH levels decrease substantially, and the corpus luteum begins to release progesterone hormone (Figure 1). Progesterone and estrogen work together to thicken the lining of the uterine wall (called the endometrium), to allow a fertilized egg to implant itself. [1, 4, 5]

Days 25-28

All hormone levels begin to drop, and if the egg (ovum) is not fertilized by sperm, the corpus luteum will break down and shed itself along with the cells of the uterine lining, which appears as menstrual bleeding and the start of a new menstrual cycle.

It is during the latter part of the Luteal Phase that you are likely to experience the symptoms of Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) like bloating, weight gain, headaches, and mood changes. Some people may also experience Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) which is a severe form of PMS.

What happens if I become pregnant?

If the ovum released during ovulation (around Day 14 of your cycle) becomes fertilized by a sperm cell, the fertilized egg will implant itself in the thickened uterine wall (endometrium). The diagram in Figure 2 shows the changes in hormone levels during a cycle of 28-day if there is fertilization of the released egg. The implanted and fertilized egg will develop into an embryo, triggering the production of a hormone called human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) (see Figure 2). The hCG hormone helps to maintain progesterone production by the corpus luteum in order to support the growth of the embryo. At this stage, estrogen levels are also high to ensure the uterine lining (endometrium) stays thick throughout the pregnancy to support the embryo, and eventually the unborn fetus. [3, 6]

What happens if I take oral contraceptives (e.g., birth control pills)?

Oral contraceptives (defined as pharmaceutical medications that counteract or prevent conception, or fertilization of the egg) have the function to prevent pregnancy by stopping ovulation and the maturation of egg cells (ova). Contraceptive medications will have a progesterone-like hormone component that diminishes the body’s production of FSH and LH, which reduces a female’s ability to ovulate. Many types of contraceptive medications also have a synthetic estrogen-like hormone component. [7] The menstrual period that happens while you are taking oral contraceptives such as birth control pills is called withdrawal bleeding, and it takes place during the 7 days when you take the placebo pills (the sugar pills that have no hormones), as a result of the change in your body’s hormones levels.

Now that you understand the physiology basics of how your reproductive hormones work to bring about your menstrual cycle, we will next explain what is going on in your body when you have a dysregulated hormonal health, such as the perimenopause and menopause transitions, or when your hormonal health might be abnormal and lead to serious and debilitating conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

Keep an eye open for more evidence-based health information that we share

in our HORMONES 101 info-series.

If you want to learn more about hormonal health, and join our community of members seeking hormonal health solutions then:

-

Follow us on Social Media – LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook, X (formerly Twitter)

References

[1] The Endrocrine Society, “Reproductive Hormones,” Jan. 24, 2024. https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/hormones-and-endocrine-function/reproductive-hormonesd-endocrine-function/reproductive-hormones.

[2] M. A. Skiba, R. J. Bell, R. M. Islam, D. J. Handelsman, R. Desai, and S. R. Davis, “Androgens During the Reproductive Years: What Is Normal for Women?”; J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab., vol. 104, no. 11, pp. 5382–5392, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-01357.

[3] National Health Service, “Periods and fertility in the menstrual cycle,” 2023. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/periods/fertility-in-the-menstrual-cycle/.

[4] M. Mihm, S. Gangooly, and S. Muttukrishna, “The normal menstrual cycle in women,” Anim. Reprod. Sci., vol. 124, no. 3–4, pp. 229–236, Apr. 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.08.030

[5] Office on Women’s Health, “Premenstrual syndrome (PMS),” 2021. https://www.womenshealth.gov/menstrual-cycle/premenstrual-syndrome.

[6] John Hopkins Medicine, “Hormones During Pregnancy.” https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/staying-healthy-during-pregnancy/hormones-during-pregnancy

.

[7] D. B. Cooper, P. Patel, and H. Mahdy, Oral Contraceptive Pills. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2022. [Online]. Available: http://europepmc.org/books/NBK430882

Figure 1. Hormone changes during the average 28-day menstrual cycle without a fertilization event. FSH is Follicle Stimulating Hormone and LH is Luteinizing Hormone. Shaded gray area is the Ovulation phase, which represents when you are most fertile.

Figure 2. Hormone changes during a cycle of 28 days that includes a fertilization event (if you become pregnant), which is marked with a star.